The SDG Financing Gap

In 2015, global leaders vowed to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by 2030. Heads of state, Government and other influential global actors met once again just 5 days ago in Seville at the 4th International Conference on Financing for Development to address critical financing challenges hindering progress on the SDGs.

As the clock ticks down (t-minus 1,638 days), this gap remains in the trillions and is forecast to further increase. Should this really be the case in a world with such an abundance of capital?

Estimates suggest there is $450T (trillion) in gross global capital, with $95T annual economic output

The Scale of the Shortfall

Estimates point to $4 trillion per year. According to the UN's Financing for Sustainable Development Report (FSDR 2024), developing countries require this much additional investment annually to meet SDG targets.

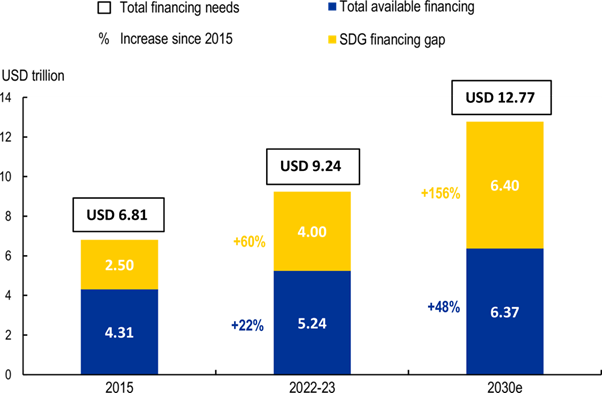

A sharp rise from $2.5T between 2015-2020, spurred by COVID-19 and other global crises, up 60% by the end of 2023, reaching $4tn today.

Africa alone may require approximately $1.3T per year to meet SDG targets by 2030.

The shortfall in SDG financing is estimated to increase to ~$6.4T by 2030 based on the growth rate between 2015-2022.

SDG financing gap, current, and forecast. Source: OECD (2025), Global Outlook on Financing for Sustainable Development 2025

Why is the gap stubbornly large?

Pandemic & Global Shocks: COVID-19 disrupted economic activity, eroded government revenues, and forced unanticipated spending globally. Since then, rising CPI, geopolitical tensions, and energy price spikes have further strained fiscal budgets. Many countries have diverted funds away from long-term development investments toward immediate crisis response and debt servicing, which has delayed SDG progress.

Debt Servicing Constraints: Many low- and lower-middle-income countries face unsustainable debt burdens. In 2023, developing countries spend a record $1.4T on debt servicing. This diverts what are already limited public resources away from SDG sectors such as healthcare, education, infrastructure, and climate resilience. Without meaningful debt relief or restructuring, governments will struggle to allocate resources toward long-term development objectives.

Private Capital Reluctance: Despite global economic output exceeding $95 trillion, private capital remains highly concentrated in developed markets. Only a small fraction flows toward SDG-aligned projects in developing countries, mainly due to perceived high risks, lack of reliable data, and shallow capital markets. Additionally, many impact-focused opportunities in emerging markets are too small or complex, making mainstream investors wary.

Underdeveloped Investment Ecosystems: The enabling environment for sustainable investment is weak in many developing economies. Uncertain regulatory environments, low institutional capacity (such as corruption etc.), and lacking impact measurement frameworks discourage investors of all sorts. Investors expect returns, often over relatively short time horizons, and the absence of strong pipelines of ‘bankable’ projects further limits investment scalability.

Solutions

Institutional push: Shifting just ~4% of institutional investor assets could cover the entire SDG financing gap of developing countries. Clearly, this is no easy task. Whilst a minor rebalancing of investment priorities may have a big impact, the question is, how exactly do achieve this rebalancing?

Blended finance: Using blended finance as a tool to de-risk (e.g. climate finance), mature markets, and build domestic economic resilience is one way of making a developing country more attractive as an investment location. Private capital is often attracted once a country, sector, or particular asset has become a commercially viable investment. The number of blended finance transactions are increasing each year, with $257Bn mobilised in total. Whilst a large number, this doesn’t touch the sides of the SDG financing gap. Blended finance vehicles should utilise tools like AI to originate smaller transactions more efficiently, whilst aggregating multiple smaller deals into pooled vehicles to make them investible at institutional scale. There are also only a small handful of private investors that have concluded 20+ blended finance transactions to date – increasing this number will rely on de-risking tactics such as provision of guarantees and market strengthening through technical assistance.

Policy & structural reforms:

Strengthen domestic taxation systems in developing countries.

Enhance concessional financing and targeted debt relief – some have even called for debt to be completely wiped for developing countries to ease the fiscal burden.

Design public-private partnerships with clear development goals and shared risks.

Reform international financial architecture to lift developing nations’ influence.

Regional SDG wealth fund: This is a more out of the box idea and requires significant liquidity in the first place to be viable – but what if instead of developing countries paying extortionate interest rates on their debts, lenders wipe this debt, instead pooling it into regional wealth funds aligned with SDG objectives? Such funds would allow developing countries to hold stable assets as investment anchors, while simultaneously making higher-risk, SDG-aligned investments within the contributing member countries. These regional wealth funds could be managed by regional authorities (e.g., an African oversight body) and overseen by creditors and multilateral institutions, with the only "repayment" obligation being the submission of strict annual impact reports - failure to report would result in the removal of debt pardons. With developing countries spending ~$1.4T annually as of 2023, regional SDG wealth funds could be one potential solution for meeting the SDG financing shortfall, especially in the longer term. Of course, this approach relies heavily on the level of governance and cooperation in given regions and is not a ‘one size fits all’.

Making up for lost time

To close SDG financing gap, it is estimated that upwards of $20T of additional investment needs to be sourced over the next 5 years. This investment will need to come in an increasingly innovative forms, with the following actors being key in facilitating this investment:

Governments: With the wealth of governments being outstripped at pace by the private sector, more efficient mobilisation of domestic resources and strategic deployment of public resources is necessary. In parallel, international cooperation platforms, such as forums, multilateral summits, and global SDG accelerators must move from rhetoric to accountability, ensuring commitments are backed by effective implementation and measurable outcomes. Policy and reporting frameworks in developed countries and regions should put much greater emphasis on integrating circular economy principles, inclusive growth, and social equity at the design stage. Increasing wealth inequality is a growing issue which falls largely at the hands of governments.

DFIs & donor agencies: Use innovative vehicles like blended finance to mobilise private capital at scale. Carefully design funds based on investor appetite, purpose, and asset risk profiles – and have funds work alongside one another to strengthen market capacity for investment and pool in investor capital. To achieve systemic impact, careful product design, marketing, and risk-sharing instruments are essential, as is a commitment to transparency and long-term outcomes.

Institutional investors: Institutional investors, managing trillions in global assets must increase allocation towards SDG aligned investment opportunities. Sustainable investing efforts have increased in recent years, and despite several challenges such as such as data inconsistency, short-termism, and regulatory lethargy, efforts must continue from all involved stakeholders to further sustainable investment mandates.

Global policymakers: Commitments made by actors such as governments and international bodies, and beneficiaries must be 1) Clear (tied to data), actionable, and tailored 2) Monitored accurately and on a timely basis – the provision of high-quality data, and transparency of reporting will be crucial. Standardised, simplified reporting frameworks with assistance from digital tools (and artificial intelligence) should help reduce barriers to investment by streamlining ESG due diligence and lowering costs. Simultaneously, spelling out financial upsides of sustainable, long-term investing will help shift mindsets and broaden market participation.

Sources

BII, 2025. Practical guidance to scale blended finance. Available at:https://www.bii.co.uk/en/news-insight/insight/articles/practical-guidance-to-scale-blended-finance/

Capital as a Force for Good, 2022. Available at: https://www.forcegood.org/frontend/img/2022-report/pdf/All_the_Money_in_the_World_20220906.pdf

OECD, 2025. Global Outlook on Financing for Sustainable Development. Available at: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/global-outlook-on-financing-for-sustainable-development-2025_753d5368-en/full-report/preparing-post-2025-transformation-amid-geo-economic-tensions_7f022612.html#title-2440b2a97f

UNCTAD, 2024. Financing Sustainable Development Report. Available at: https://unctad.org/publication/financing-sustainable-development-report-2024

UNCTAD, 2023. Investment trends Monitor: Available at: Finhttps://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/diaemisc2023d6_en.pdf